Poor Child Health with Prosperity

Neeraj Kumar and Arup Mitra

Neeraj Kumar, a member of the Indian Economic Service, Deputy Director, Ministry of Finance, Government of India and a Ph.D. scholar at the Delhi School of Economics

Arup Mitra, Professor of Economics with the Institute of Economic Growth, Delhi, India.

There is no conflict of interest.

Abstract

This study based on cross-sectional information examines the hypothesis that prosperity does not necessarily result in good health. Evidence on the role of economic growth in improving the child health indicators is insufficient. While growth may be important for generating resources for provision of better health care facilities, factors that influence consumption pattern will have to be perceived beyond the affordability framework.

Poor Child Health with Prosperity

Hypothesis

A major stylized fact in the context of child health and nutrition relates to a significant decline in poor health outcomes (such as under five mortality, nutrition related deaths, anemia etc.) with an increase in income per capita. However, an equally strong hypothesis emerges to indicate that prosperity does not necessarily result in good health. Cumulative child health indicators of prosperous nations are quite disturbing, though they observe better mortality indictors. A number of diseases associated with economic richness are observable in high income countries. The consumption pattern is more important than economic growth to improve the child health outcomes. Hence, factors which impinge on consumption pattern rather than the level of consumption are to be considered. Unless awareness and interventions are made at societal level the ‘curse of prosperity’ cannot be overcome. In the backdrop of this viewpoint, we assess the relationship between a number of child health indicators and GDP per capita across 71 countries for which recent and comparable data is available. The definition of variables and the sources of information are listed in Table 1. The graphical plots, correlations and factor analysis are carried out to have a thorough understanding of the relationship between child health outcomes and per capita income.

Child health indicators and per capita income across 71 countries

Table 1: Data and Definition(s)

Variable | Definition | Year/Source |

GDPPC | GDP per capita (current US$) – GDP divided by midyear population. Data are in current U.S. dollars. | 2019 / World Bank |

Stunting | Moderate and severe: Percentage of children aged 0–59 months who are below minus two standard deviations from median height-for-age of the WHO Child Growth Standards. | Latest available (2015-2019) / UNICEF / last updated July 2020 |

Underweight | Moderate and severe: Percentage of children aged 0–59 months who are below minus two standard deviations from median weight-for-age of the World Health Organization (WHO) Child Growth Standards. | |

Severe wasting | Percentage of children aged 0–59 months who are below minus three standard deviations from median weight-for-height of the WHO Child Growth Standards. | |

Wasting | Moderate and severe: Percentage of children aged 0–59 months who are below minus two standard deviations from median weight-for-height of the WHO Child Growth Standards. | |

Overweight | Moderate and severe: Percentage of children aged 0-59 months who are above two standard deviations from median weight-for-height of the WHO Child Growth Standards. | |

Anemia U5 | Prevalence of anemia among children (% of children under 5)-percentage of children under age 5 whose hemoglobin level is less than 110 grams per liter at sea level. | 2015 (latest available) / World Bank |

U5MR | Mortality rate, under-5 (per 1,000 live births) – Probability per 1,000 that a newborn baby will die before reaching age five, if subject to age-specific mortality rates of the specified year. | 2019 / World Bank |

Death_CD&Nut | Cause of death, by communicable diseases and maternal, prenatal and nutrition conditions (% of total) – Cause of death refers to the share of all deaths for all ages by underlying causes. Communicable diseases and maternal, prenatal and nutrition conditions include infectious and parasitic diseases, respiratory infections, and nutritional deficiencies such as underweight and stunting. | 2019 / World Bank |

Evidence

While stunting and anemia among children below 5 years of age, under 5 mortality and death caused by communicable diseases and maternal, prenatal and nutrition conditions bear a negative correlation of nearly 0.60 or more with per capita income, prevalence of underweight children are not as strongly associated with growth (Table 2). On the other hand, prevalence of wasting and severe wasting in children are weakly correlated with per capita income, though the nature of association is still seen to be negative. Further, the percentage of overweight children and income unravel a positive correlation.

Table 2: Correlation Matrix

| GDPPC | Stunting | Under Weight | Wasting | Severe Wasting | Over Weight | Anemia U5 | U5MR | Death cd&nut |

GDPPC | 1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stunting | -0.60 | 1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Under weight | -0.50 | 0.79 | 1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wasting | -0.23 | 0.35 | 0.80 | 1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

Severe wasting | -0.12 | 0.28 | 0.64 | 0.90 | 1.00 |

|

|

|

|

Over weight | 0.44 | -0.52 | -0.70 | -0.53 | -0.30 | 1.00 |

|

|

|

Anemia U5 | -0.61 | 0.48 | 0.57 | 0.44 | 0.34 | -0.59 | 1.00 |

|

|

U5MR | -0.61 | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.32 | 0.26 | -0.49 | 0.87 | 1.00 |

|

Death cd&nut | -0.64 | 0.63 | 0.56 | 0.30 | 0.19 | -0.54 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 1.00 |

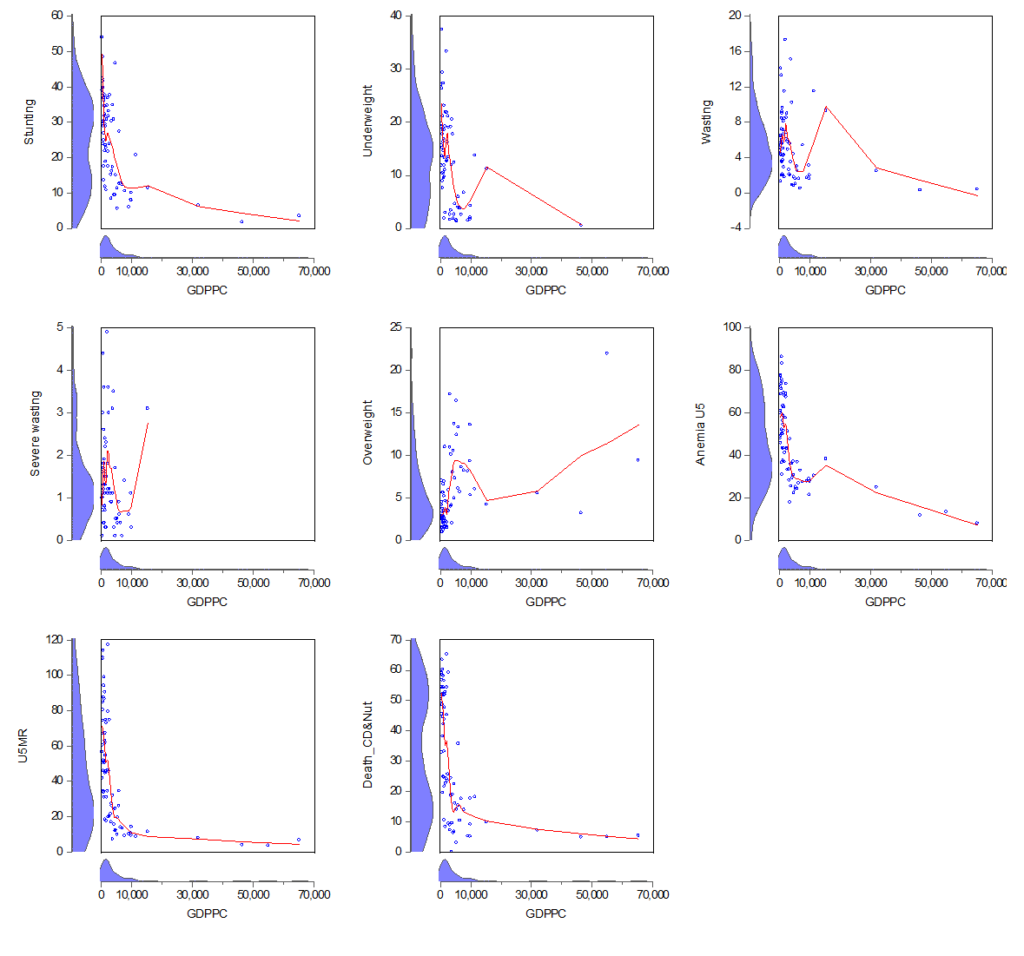

The graphical plots below show a negative linear or a hyperbolic relationship between per capita income and only three of the child health outcome indicators (stunting, under 5 mortality and the percentage of death caused by communicable diseases and maternal, prenatal and nutrition conditions). The rest of the indicators bear humps in the child health-growth constellation. Surprisingly, the key cumulative child health indicators such as prevalence of underweight, wasting and severe wasting in children below 5 years of age show unexpected penurious position of relatively higher income countries. Further, the prevalence of overweight / obese children keeps on amplifying as countries move on high income trajectory (the upward sloping income-overweight trend at higher income levels shows worrying signals about consumption pattern in rich nations). Though higher income countries are able to control their nutrition related mortality indicators possibly due to better tertiary/curative health care facilities, they seem far from achieving desired outcomes in terms of cumulative child health indicators such as underweight, wasting, severe wasting and anemia despite being in economically better position (the ‘v’ effect of prosperity on these indicators at upper middle / higher income levels before declining trend is clearly visible).

Graph 1: Scatter plot with kernel density axis borders and Nearest Neighbor Fit (the nearest neighbor fit is nonparametric regression method that fit local polynomial)

Factor Analysis

The factor analysis of the variables is indicative of only two significant factors between which the first is the most dominant one with an eigen value of 5.13 while the second one is only marginally significant (Table 3). In factor 1 anemia among children below the age 5, under 5 mortality and death due to communicable diseases and maternal, prenatal and nutrition conditions take a very high factor loading each, suggesting that these variables move together across countries. They are negatively associated with per capita income though the factor loading of income variable is not as high as that of the child health indicators. This would caution us from assigning the entire credit of achieving better mortality outcomes to economic growth. The cumulative child health indicators such as stunting, underweight, wasting and severe wasting have moderate to low factor loadings indicating their weak connections with growth. In other words, with improvements in growth these indicators tend to decline only sluggishly. The most striking point is borne out by the fact that the factor loadings of both growth and the percentage of overweight children have the same negative sign, indicating a positive relationship between the two, that is, the curse of prosperity. At the most, one may argue that it is the better curative health care facilities and not preventive measures that might have led to better mortality indicators. Consciously employing money towards good health through healthy consumptions patterns seems to have little to do with income levels across the nations. Higher income levels alone translating to desired child health outcomes seem to be a remote possibility in the present scenario. This has equally strong implications in terms of cognitive development of children, quality of human capital, productivity of workforce and long term growth of any nation.

Table 3: Factor loadings (pattern matrix) and unique variances

Variable | Factor1 | Factor2 | Factor3 | Factor4 | Factor5 | Uniqueness |

GDPPC | -0.561 | -0.045 | -0.431 | -0.110 | 0.118 | 0.472 |

Stunting | 0.361 | 0.169 | 0.868 | 0.038 | -0.010 | 0.087 |

Underweight | 0.303 | 0.625 | 0.638 | 0.292 | 0.024 | 0.025 |

Wasting | 0.157 | 0.941 | 0.150 | 0.217 | -0.019 | 0.021 |

severe wasting | 0.104 | 0.932 | 0.095 | -0.124 | 0.011 | 0.096 |

Overweight | -0.403 | -0.315 | -0.347 | -0.503 | 0.010 | 0.365 |

anemiau5 | 0.878 | 0.264 | 0.147 | 0.172 | -0.041 | 0.106 |

u5mr | 0.876 | 0.155 | 0.279 | 0.006 | 0.018 | 0.130 |

death_cdnut | 0.869 | 0.093 | 0.331 | 0.095 | 0.017 | 0.118 |

Eigen Value for Factor 1 and Factor 2 are 5.13 and 1.57 respectively; number of observations is 63.

Conclusion

On the whole, evidence on the role of economic growth in improving the child health indicators in a holistic sense is rather insufficient. While some of the indicators are dependent on growth to generate resources so that households can access better health care facilities and become more development conscious, certain other indicators depend hugely on factors that influence consumption pattern. These factors will have to be perceived beyond the affordability framework. Health awareness programmes, mothers’ education and knowledge on child nutrition norms, food value and nutrition content are crucial for determining healthy consumption habits which in turn will contribute to the making of a capable and productive work force in the years to come.